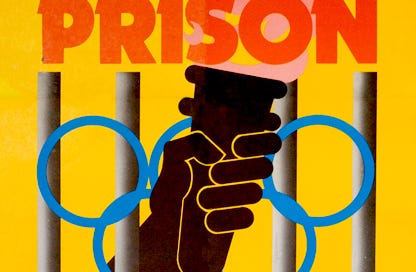

In 1980, All Of The Athletes At The Winter Olympics Were Sent To Prison

The legacy of the 1980 Winter Olympics is a medium-security prison.

Here’s my usual spiel: If you’re enjoying the newsletter and want to support it, please subscribe. I’ll leave this button right here. You know what to do.