Meet Sid Oglesby, The First African American NCAA Gymnastics Champion

A Q&A with the 1964 NCAA long horse champion

If you’re enjoying this newsletter and wish to support it, please consider subscribing!

In late 2019, when I interviewed Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi, a New York-born South African painter and artist, she talked about her Heroes series and mentioned the portraits she had painted of important figures in Black gymnastics history. Some of the names she mentioned were familiar to me, gymnasts such as Luci Collins, the first Black woman named to a U.S. Olympic gymnastics team, and Betty Okino, a world and Olympic medalist who competed in the early 90s. But Nkosi also mentioned names of gymnasts that I wasn’t familiar with, like James Kanati Allen and Sid Oglesby, two Black male gymnasts who competed in the 60s.

(This is now the third newsletter this month in which I’ve brought up Nkosi and her work. If you’re starting to think that I may be a Nkosi stan, well, you’re not wrong. Check out the two newsletters I published about her amazing work earlier this month.)

Speaking with Nkosi made me realize that I hadn’t dug deep enough into the history of Black achievement in gymnastics. I only ever went back as far as the late 70s and early 80s to gymnasts like Collins, Dianne Durham, the first African American gymnast to win the U.S. all-around title, and Ron Galimore, a member of the 1980 Olympic team. But of course, that’s not where the history of Black excellence in the sport of gymnastics started. Black gymnasts have been ascendant in the sport well before 1980.

Twelve years before Galimore and Collins were named to the 1980 Olympic team that didn’t compete in Moscow due to the U.S.-led boycott of the Games, James Kanati Allen, who is of African and Native American descent, was named to the 1968 Olympic team. At the time, the gymnast was on the UCLA gymnastics team and working with the legendary coach Art Shurlock. Kanati Allen also placed third in the all-around at the 1967 NCAA championships. After his gymnastics career ended, he went onto the University of Washington where he earned a PhD in physics. (He died in 2011.)

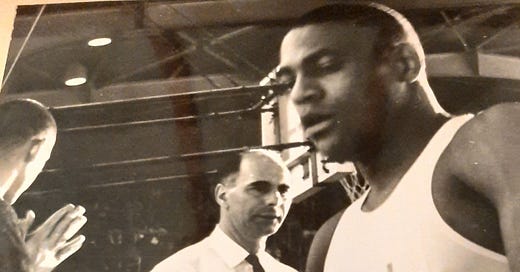

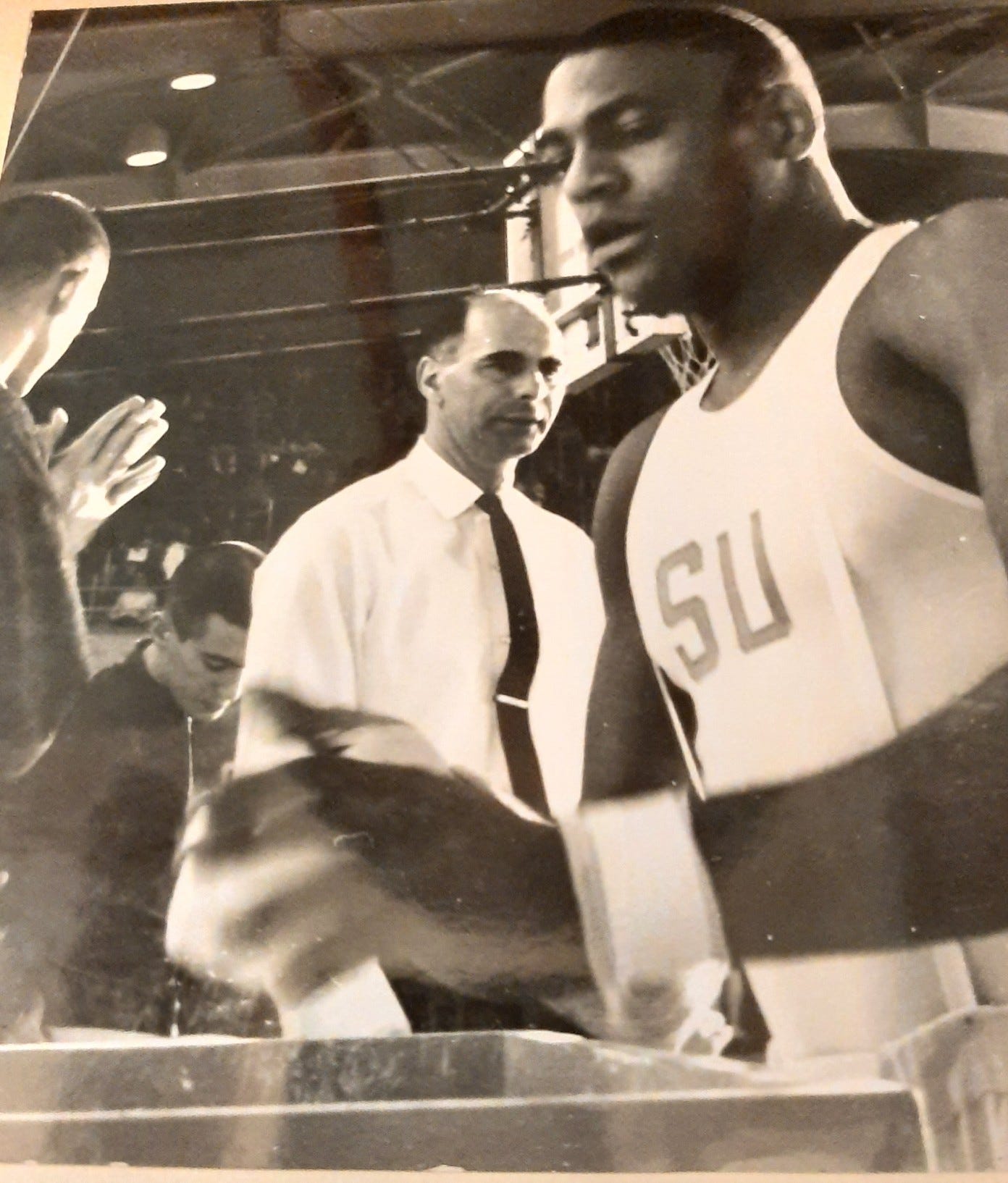

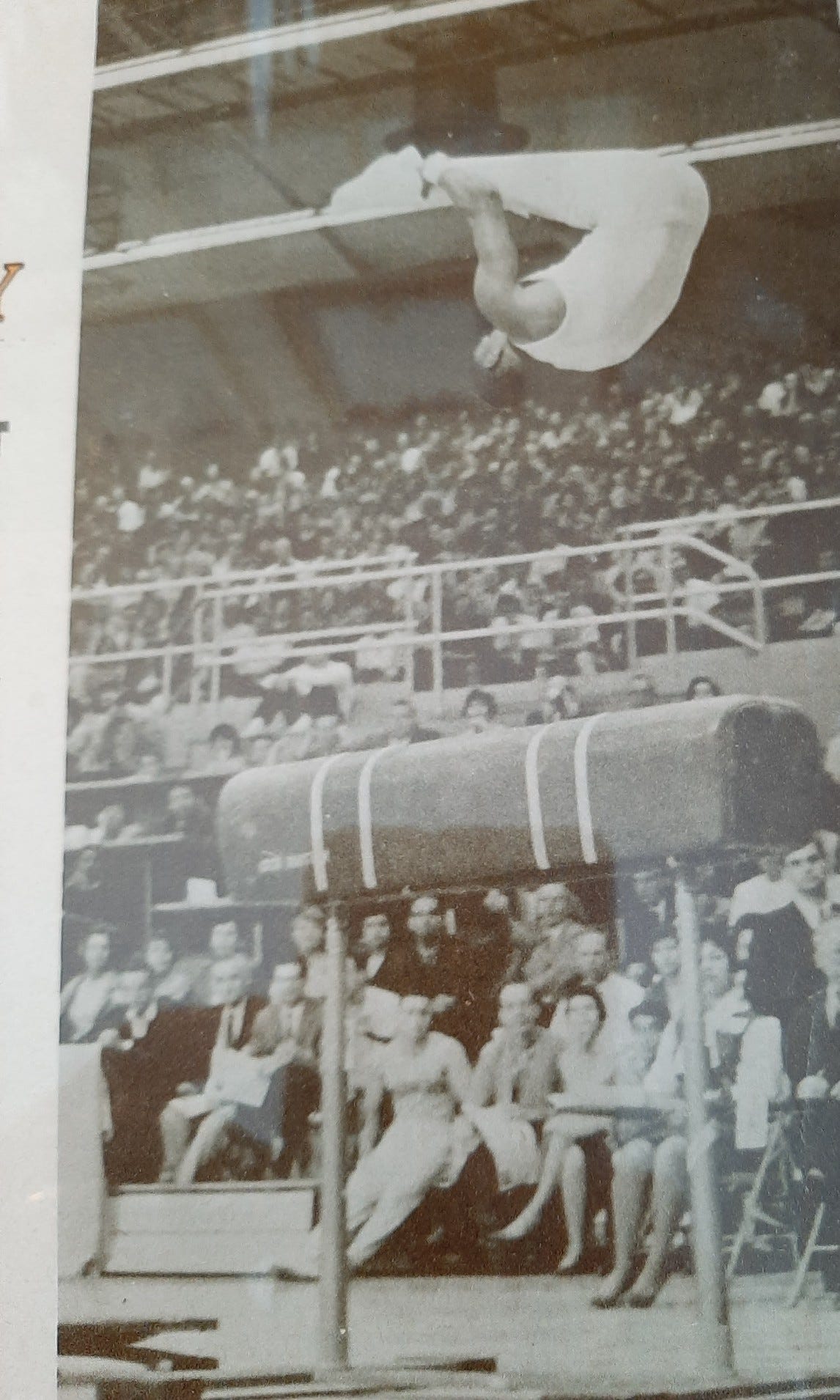

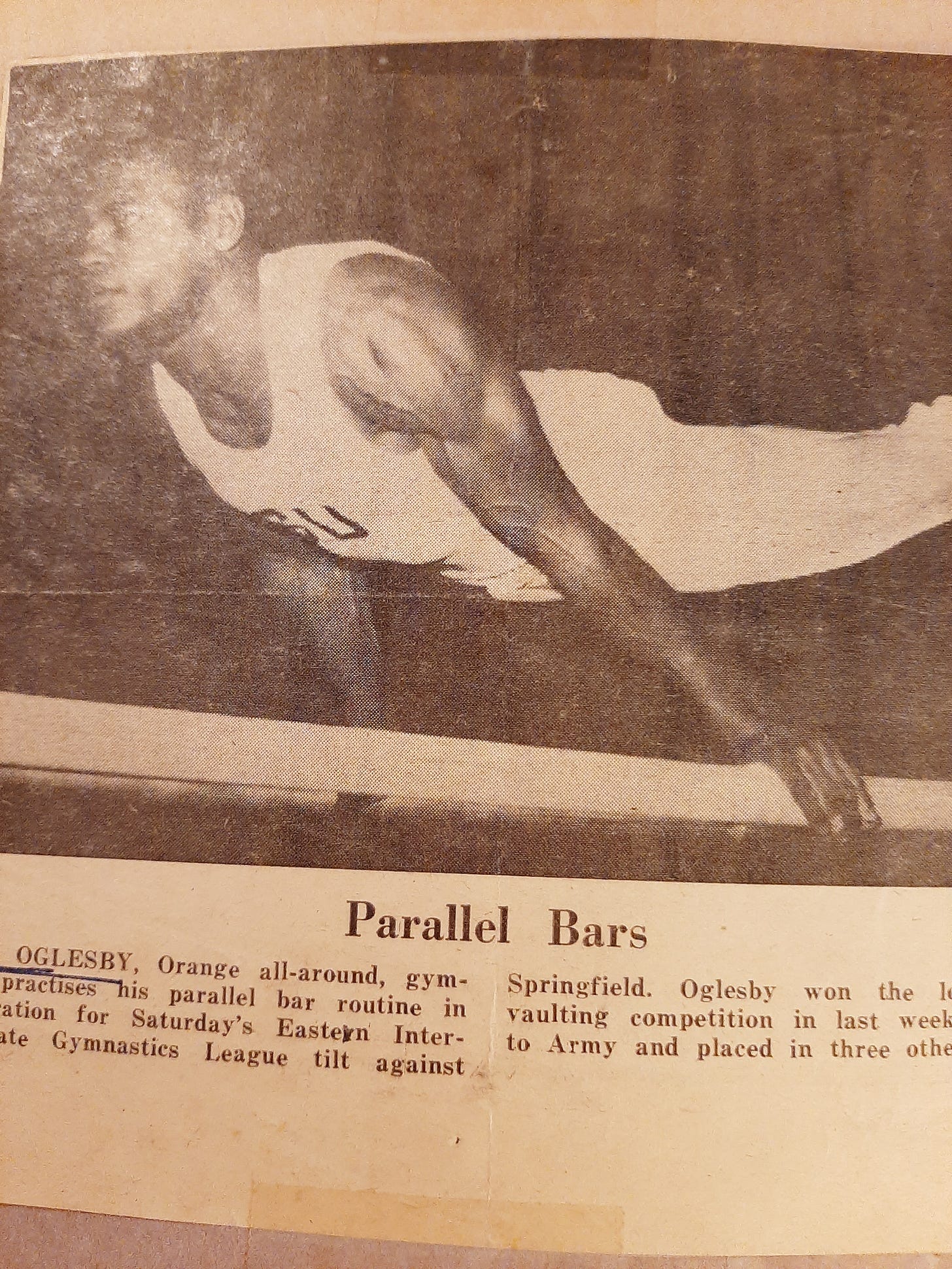

Four years before Kanati Allen’s historic achievement, Sid Oglesby was pulling off a first of his own. In 1964, the senior at Syracuse University took top honors on the long horse at the NCAA Championships in Los Angeles, making him the first Black gymnast to win an NCAA title. Oglesby also distinguished himself through activism, both during his athletic career and after. In 1964, he joined a cohort of Black athletes at SU to demand that the school stop competing with other universities where the students were still racially segregated.

After graduating, Oglesby eventually embarked on a career in politics and brought his activism with him. In 1995, while he was a member of the Onondaga County Legislature in New York State, Oglesby was arrested while protesting the diversion of traffic—and pollutants—to a low income, predominantly Black housing project in order to avoid a federal pollution monitor. “I’m being arrested because of the public plan to distribute pollution in the Black community,” Oglesby said when he was arrested. Oglesby was also the first African American named to the Commissioner of Jurors. He retired in 2015.

I reached out to Oglesby, who still resides in Syracuse, and asked if he’d be open to speaking with me about his life and career, both on and off the mat, and he graciously agreed.

The conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Dvora Meyers: How did you get started in gymnastics?

Sid Oglesby: It was really quite accidental. My brother, who was in gymnastics at the time in Jersey City, bet me that I couldn't climb the rope, which he could. And I failed at it after going about halfway up...In any case, I was annoyed so I decided to succeed in it. I got into gymnastics.

When I look back, I was thinking, ‘Well, did I ever compete against a Black person in college?’ and I couldn't recall. And I thought about it. I said, ‘Well, that's not possible. There were a lot of Black gymnasts.’...And I began to think more and more about that question. I looked back on one of my high school teams, and I would say 60% of the gymnasts in high school were Black. And then I thought about it further, as it were, why is that? And it crossed my mind that that's because there was equipment, and a number of teams available at the time, such as the YMCA, AAU, and again, in my high school.

I started with a guy named Martin, who had a German turnverein club, and I used to go there and practice gymnastics. And, frankly, I don't know what I would have done had that German turnverein club not existed. There's one here in Syracuse as well, and I am always kind of amused at that, because that was a site of gymnastic sports for Blacks.

DM: Your college gymnastics career took place in the 60s, which is a time of transition for the sport in the U.S. I remember reading in some history of American gymnastics that in the early 60s, the ratio of male to female gymnasts was something like 6:1 but a decade later, it had completely flipped, and the ratio was 6:1 for female to male gymnasts. Several things had happened in those years, most notably the rise of Olga Korbut and then Nadia Comaneci as the two first global superstars of the sport, but you also had Cathy Rigby who won the first world championships for the Americans in 1970.

SO: It was a club sport [for the women], as opposed to an NCAA scholastic sport. And interestingly enough, if you follow the timeline, many, many [men’s] scholastic gymnastic teams have collapsed. There are fewer and fewer scholastic teams now.

DM: At the end of this season, they're [men’s NCAA gymnastics] going to have 12 Division I teams left, but when you competed, there were over 100 programs and now we’re getting really close to single digits.

[Ed. note: Earlier this week, my longform feature about the decline of men’s NCAA gymnastics was published at Defector if you’re interested in learning more about this topic.]

SO: Many of my friends were football players. I competed against 42 teams at one point in time, At the same time, when they went, they competed against one. I used to tease them about that all the time.

DM: When we talk about Black athletes in college sports, the sports we mainly discuss are basketball and football. But it was a different situation when you were competing; all this TV money hadn't really come into those sports yet. Nowadays those sports can be really profitable for schools and the NCAA, and so the discussion of Black athletes about being exploited has really centered on the fact that they’re not getting paid while college football and basketball coaches are the highest-paid public employees in the country, which is crazy. And in the past year, the conversation around the exploitation of Black athletes has been about they’re unpaid and they’re being pressured into playing in the middle of a pandemic so that the schools and all of the other financial stakeholders don’t lose money.

Back in your day, the exploitation of Black athletes looked a little different. I know that in 1964, you signed a petition with other athletes at Syracuse to get the school to stop competing against universities that were still segregated. I wonder if you see any parallels in your situation back then to what Black athletes are now experiencing.

SO: We had protested against this in 1964, against playing schools that discriminated against Black people...There were 17 athletes of all sorts. Obviously, I was the only one from gymnastics, but a lot of basketball players and football players [participated]. And we all signed a letter and we promoted the university to do this.

Syracuse was put on the map by Black athletes and I've always been annoyed that not enough credit was given to them. The fact of the matter is, you look at Jim Brown and Ernie Davis, Floyd Little, myself, gymnasts and wrestling, this is across the board. People came to know Syracuse University nationally as a result of that. It promoted the school and people came. It became a school nationally known because of Black athletes.

DM: You see that happen quite a bit when you're watching March Madness, and you see this school you had never heard of in your life and then they're in the Sweet 16. The sports, whether or not they bring revenue, can help universities really gain a national profile. You weren't making money for the school because, at the time, the lucrative TV contracts didn't exist yet, but you were clearly performing another service for the university.

You were a student during the 60s, which was a period of highly visible Black athlete activism: Harry Edwards and his Olympic Project for Human Rights; John Carlos and Tommie Smith’s Black Power salute at the 68 Olympic Games; the push to have more Black college coaches. I know you've already told me a little bit about the letter that you signed but can you speak a bit more about the athlete activism of that period and becoming more politically conscious around that time?

SO: In the context of Syracuse University, that's the one I speak to, the human rights issues and the civil rights issues were all beginning to bubble to the surface. And we had a lot of civil rights issues going on nationally, as well. I think what happened is that Blacks found a platform. And they found that platform because I think their experiences—their personal, everyday experience, both on and off campus—distinguished them as Black persons. Whereas on a Saturday when you were performing athletics, everybody loved you but [then after] you couldn't go to certain parties. We hit on a little social network, which was largely connected to the Black community, etc. When you combine that with the civil rights movement, Blacks felt, I think, an inherent obligation to say something about what was going on in their own lives.

And that was expressed through, as I said, the 17 athletes who saw this in the schools they were participating against. Don’t forget but right after that, Ernie Davis, who this university celebrated, couldn't even sleep in the same hotel when they [the team] would travel to certain sporting events, and the team finally stood up. I can remember when we all met with the coach of the football team in his office, and we were discussing what we wanted to do. And he said to me, ‘What are you doing here?’ Because he misunderstood or didn't understand that a particular athlete, what team you were on, had nothing to do with human rights and civil rights. He thought it was just football people he should be speaking to, but we [the Black athletes] saw it quite differently.

Jim Nance was a Black football player. He was an All-American football player. And he was also a two-time NCAA wrestling champion. He never got the credit that [he deserved]. And I always resented that. I resent it, because he, in fact, brought a lot of credit to the university. He also went on to become a professional football player for the New England Patriots. [Ed. note: At the time, the team was called the Boston Patriots.] So it was the context that we were in, both in terms of human rights, as well as civil rights and Blacks' participation on that stage at the time; that was a platform that was available.

DM: I think you commented in one of the stories I read that you didn't feel like you were treated well, by all the members of your gymnastics team, even though you were doing so well for them.

SO: It was one person in particular whose name I won't mention, but my birthday is February 20. The reason that's important, the gymnasts who are still around and including my old assistant coach, take me to lunch on my birthday. Each time we do this, they bring up this person's name, because I got into a physical altercation with them. And the physical altercation was that I was doing a handstand on the parallel bars. And he thought it was okay to tell me to get the hell down from the apparatus. I did get down and I commenced to kick his ass. There was a big brouhaha on the team, and my coach didn't know what to do with it. And I felt a little offended by it because I was scoring first place. Best he ever scored was fifth place. He was always acting like he was better [than me]. The rest of the team I did well with. I became the captain of the team.

But I have forgiven my coach, he just didn't know how to handle it. In fact, if anybody should have been kicked off the team, it should've been him. But he wasn't and I wasn't. I went on to continue to score first places then he went on to continue to score fifth.

DM: In terms of some of the conversations with teammates and rivals, is it fair to say that you had to really prove yourself to your team more than a white athlete would?

SO: I think I had to prove myself in everything.

I never thought in racial terms in a serious way until I got to college. I grew up in Jersey City, New Jersey; [it was] very diverse. When I got to college, I felt the distinction of who I was versus other people, all the time, everywhere. And there were issues here that were profound. And so I began to see and think more racially, and it's been with me most of my life.

DM: What was different about the environment in Syracuse vs. Jersey City?

SO: It was very explicit. The architecture of the community, and I don't mean physically, but psychologically, was such that it was segmented with Blacks on one side of the town, Italians lived on another side of the town, Jews lived on the east side of the town. I always lived on the west side of the town, the University was in the middle of the town. And you know, the twain shall never meet. That's how it was.

[Ed. note: Now we’re discussing his championship in 1964 and his near win—or near miss, depending on how you view it—in 63.]

SO: In 63. I lost that in a very small way. 63 had more impact on me than the 64 win.

DM: Can you talk about what happened in 1963 that you're referring to?

SO: Well, 63. First of all, I had already won the [eastern] conference championship in both parallel bars and long horse. When I got to Pittsburgh [where the national championships were that year] I slipped on the parallel bars mostly because when I thought I was almost finished. I took my mind off what I was doing and I had a break. And I never forgave myself for that. Never get ahead of yourself.

[Ed. note: We’re now talking about the long horse in 1963 when he almost won the title]

What happened was that they had already announced that I won the championship. And I was glad about that. And then they said, ‘Oops, we forgot someone else who must have been running around, didn't compete and didn't have a chance to go yet.’ So they gave them a chance to go. And as they threw up some scores, when you pulled the total over the days together, he beat me I think by 12 hundredths of a point or something like that. That always affected me more.

Because of that in 64, in California, Los Angeles, when I won the championship, it never really had such an impact on me. For many years, it never did, really.... I don't know, maybe I was so engaged in the struggles for life. I knew I had won, but I never felt great about it. I never celebrated, like you would think most people would. In fact, I've been thinking about this in the latter part of my life. Why not? And I don't really have an explanation for it. But as time went on, I have other friends and we talk about these things. And that's how we got to the, what they call the reconciliation, that's what I call it when the university honored me at a football game. [Ed. note: This happened in 2007.] But I often wondered about that. It made me think about being the first Black gymnast [to win an NCAA title] because I never thought about it for a long time [about what it meant] to win a national championship.

When you told me about this lady [Nkosi] who you learned [about me] from...The fact that she was in Johannesburg, South Africa and was aware of me. And yet there are people who are right here in this country [who don’t know].

DM: Speaking of Africa, can you talk about your trip there as a gymnast?

SO: It was with the AAU, which is the American Athletic Union. They approached me, as I recall. They wanted to send a team through the State Department, a goodwill tour to Africa. To put it in historical-political terms, I think they did it because China was doing the same thing. From a political point of view, they were competing with China as a country to get some exposure in Africa. So half the team was Black, I think; it was four Blacks and four whites, I believe.

It was a beautiful experience.

But I learned that my colleagues, my teammates, transported their view of the world to Africa, which didn't fit, because [there] they were in a minority. So [they were] constantly getting in trouble, or having problems adjusting.

My white teammates’ American values and attitudes were transported to Africa where they expected a similar structure of racialism. The racism in Africa was structured around classism because everyone was Black. In America, racism is based on color, which determines everything: how you behave and how others behave towards you. Africans did not seem to have internalized inferiority. One example that still stands out to me is that when we had servants provided at the residence where we stayed, I would tip them but some teammates would not because they were behaving like they expected it.

Now, one of the things I remember, particularly in Malawi, I remember we had these private buses, like a Volkswagen bus and they would take us to various little villages to compete to do an exhibition. And there would be all these people walking along the road. And finally, we asked ‘What are these people doing?’ They were walking the next day to see us. And I was always impressed by that and some of the songs they would sing of appreciation. I actually looked through some articles that I had about it. There's a picture of me doing a trick in gymnastics in Malawi.

The trip to Africa really changed my mind and orientation…I no longer had to think as a minority because of the color of my skin and have that psychologically define me. I could define myself and behave accordingly. Dual thinking is due to the psychological fissure one develops because of racism--how you think of yourself and behave and how others think of you and behave. I got rid of the mental fissure by being one person in all racial circumstances and demanded the same from others.

DM: Can you talk about getting into politics in Syracuse and running for the legislature?

SO: First, before I ran for the legislature, I ran for city council. I ran and lost in the fourth district. And then I was appointed to the council at large for the whole city. And that was an interesting experience, because I eventually didn't wait on the reappointment. I did some things there, but I wasn't there long enough to really have an impact. But then subsequent to that, I ran for the county legislature and I won every time since then. And I became the Democratic floor leader.

I was initially in the minority and then we became even and I didn't like the notion of being called Minority Leader. So I got them to change it. It's still called the floor leader. I was always proud of that, because what's “minority” got to do with it? You're leading your side of the aisle, and it was 12-12.

I was there for at least five years or six years in the legislature before I became Commissioner [of Jurors].

DM: Can you talk about the time you were arrested protesting car pollution around the Pioneer Homes?

SO: The highway cuts through the middle of the Black community and the exit ramp gets right off at the Black community. [You] make a left-hand turn and it goes right up to the university. The dome handles 35,000 people during football games and basketball games, etc. big events and cars are all trying to get as close to the university as possible. That meant they had to go through what we call Pioneer Home, which is a low-income, Black neighborhood. The traffic should have gone into the parking garage, but instead of going to the parking garage, they were getting off there, and then parking on the streets near the Pioneer Homes, because it was closest to the [Carrier] Dome.

The federal government had found that the pollution of carbon dioxide was very, very high there and so what they did was they penalized the county. They penalized the county by increasing the price of gasoline [by]10 cents, I don't remember exactly. And they also, in addition to that, they put up [CO2] monitors right at that exit so they could determine from the monitor whether it was increasing or decreasing.

The county executive decided he wanted to get his transportation people to move the monitors, two blocks down from the exit and I protested that. ‘…The pollution is still there whether the monitor has moved two blocks or not’. And I did it with another legislative friend of mine, Carmen Harlow. He organized it. They decided to arrest me, I didn't plan to get arrested. It was interesting, because the jailhouse is one building away from my office. So when they brought me there, they were gonna charge me And they decided they couldn't do this because I was a floor leader; it would make this a bigger issue than what it was. So they decided to drop all charges.

DM: This tracks since a lot of pollution has been diverted into low-income and minority communities. They put an off-ramp, which no one wants to live next to, in the Black community.

SO: So the suburbanites can come in and earn a living.

DM: And go to a football game.

SO: Or a basketball game and get immediately back onto the highway.

DM: And leave their exhaust fumes behind.

DM: Do you follow gymnastics anymore? What is your attachment—if any—to the sport?

SO: When I'm scrolling, I usually read titles both on the cell and the internet and if [gymnastics] it appears I become interested. And really that's about it. Men's gymnastics has gone here [in Syracuse]. The only connection I have is with my old gymnastic friends and teammates.

You provoked my thinking about this in my own life and things of that nature. I've done a lot of first things, which always surprises me. I didn't do things to be the first, but it turns out that I was the first. Even in the legislature, when they made me floor leader, the first elected Black floor leader...Then I became the first black Commissioner of Jurors. I never thought about it before. Then I became the first Black president of the Jury Association for the whole state in New York.

I have a computer room which is loaded with all my plaques. My wife says to me, ‘Are you going to take a trip down nostalgia [lane]’. Well, you know, the honest to god truth. I never had them up until this year. I had them in boxes in the basement.

DM: What made you want to put them up now?

SO: We did it maybe a month or so ago...Maybe cause I don’t have to work or what have you. I don’t have to look forward. I can now look back….I didn’t talk about it early on. As I said, I didn’t really deal with it very much.

I told my children in NYC that I put them up and they were glad. Also I sent pictures of them to my nephew in Singapore who has boys in gymnastics, and they were thrilled. Also my nieces in Skaneateles, NY are into gymnastics and I sent pictures to them and they were thrilled. Their dad showed them how to download my exploits and now they send me pictures of them practicing gymnastics with a reminder that I now have competition.

Here’s what Sheena Oglesby, Sid’s daughter, had to say about her father and his accomplishments:

My sister and I always grew up celebrating our Dad's gymnastics career, but the way I frame his successes in my mind has definitely become less one-dimensional as I've gotten older.

As kids we were proud and impressed enough to use it as constant "Show and Tell" material, and begged him to do flips well past the age where one would probably medically advise [doing them].

But I didn't begin to appreciate the nuances of his contribution and experience until I was older (probably in college at Syracuse myself). I realized the impact he'd had on the sport, and the truly impressive feat he'd been able to achieve from a physical & mental place, but also socio-politically and culturally.

I'm so proud of his achievements, and I've appreciated the recognition he's received for it (albeit later in life), but when he and I discuss it now, it's through more of a psychological lens than anything.

I have a photo of him at my desk - on the winner's podium, plaque in hand, the only Black person in sight. To me, now, I look at it and see an image of an historic event, and an image of the pride, the pain, and the isolation he experienced. It's all there in his face, and in his story. It really captures both the beauty and the burden of "going first.”

The isolation that Sheena described seeing in the photo of her father on the winner’s podium, surrounded by white gymnasts is something that Sid said that he keenly felt during his gymnastics career. He emailed this to me late last night and I’m sharing it here with his permission:

“Gymnastics and race was the most lonely experience in my life. It formed me both for better or worse. I never shared any of my feelings with my children because I didn't want to skew their perceptions about life as a Black person but arrive at their own conclusions.”

During the course of our conversation, Oglesby spoke about being disappointed that the Black male gymnasts of his era were largely forgotten or overlooked. The blame for this lack of recognition belongs to people like me in the media who have consistently failed to shine a light on earlier generations of Black gymnasts.

While this email newsletter will hardly right this wrong, I do hope it helps, in a small way, to bring Oglesby some of the recognition he deserves for his contributions to gymnastics and to life outside of the sport.

Absolutely loved this interview!